The World After Dinosaur Extinction

About 66 million years ago, an asteroid at least 10 km in diameter and weighing a trillion tons crashed into what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The impact opened a 180 km crater, melting the oceanic crust and hurling thousands of tons of rock into space. As these rocks re-entered the atmosphere, they ignited and caused global fires when they hit the ground.

At the same time, the shock waves from the impact created one of the largest megatsunamis ever to hit the planet, as well as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions around the world. The lava ejected by the volcanoes released gases that created a greenhouse effect and poisoned the air, water, and soil.

As a result of the asteroid impact and volcanism, a mass of ash covered the sky and prevented sunlight from reaching the ground for about a decade, making it difficult for plants to grow. Without the sun, the planet began to cool rapidly, and drastic climate changes destroyed food chains in the terrestrial and marine environments. Within a few decades, 75% of the animals became extinct.1

This extinction (called the K-T Extinction) marked not only the end of the dinosaurs, but also the end of the entire Mesozoic Era, and ushered in a new era, the Cenozoic Era. The first period of the Cenozoic is called the Paleogene or Tertiary, and the first period immediately following the K-T extinction is called the Paleocene.

After the chaos that marked the end of the Cretaceous, the climate became somewhat more stable over time, the dust cloud that obscured the sun’s rays dissipated, the chemical components that filled the air and oceans diminished, and flora and fauna gradually began to flourish again throughout the new epoch. However, ecosystems would not fully recover until several thousand years later, at the end of the Paleocene Epoch.

Without the non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and other large predators, new doors were opened for the small animals that lived in the remains, such as mammals, to evolve.

Mammals

The first mammals lived alongside the dinosaurs from the end of the Jurassic period. They were small, rodent-like, and spent the day hiding. Only at night, when most large predators were asleep, could they come out to forage and carry out their activities.

From the Paleocene onwards, there was a great diversification of these animals. They adapted to a daytime lifestyle, broadened their diet, improved their reproduction, developed their brains and grew.

One of the animals that emerged were the marsupials, which in some parts of South America made up about 50% of the mammal species - many of them closely related to today’s opossums. For this reason, the latter are often referred to as “living fossils”. Also in South America, there are records of a second group of modern marsupials that have existed since the Paleocene - the marsupial mice.

Initially only a few centimeters long, these animals evolved into large herbivorous mammals, such as the Dinoceratas, which reached up to 4 m (13 ft) in length, and carnivorous mammals - such as the Sparassodonts.2 The mammals that went to the oceans adapted to the new lifestyle and over the course of thousands of years became the cetaceans, while those that went to the trees became the primates. By adapting to so many different environments and ways of life, the mammals became the new dominant species, along with the birds.3

Birds

During the reign of the dinosaurs, no bird had a wingspan greater than 2 m (6 ft). Pterosaurs, on the other hand, could have wingspans of up to 40 feet (12 m). After their extinction, birds were able to diversify faster than any other group of animals, allowing certain birds, such as the pelagornithids, to dominate the skies and reach wingspans of up to 20 feet (6 m).

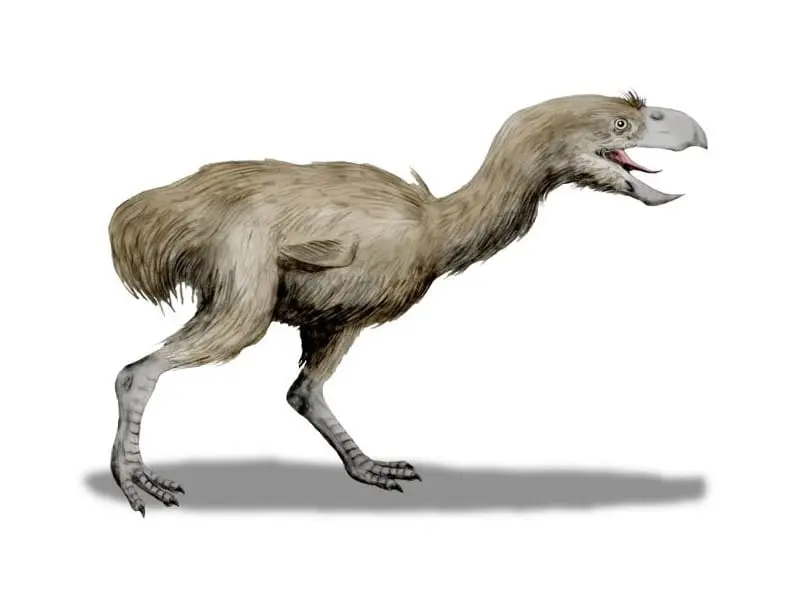

Despite this, the fossil record of birds that lived during the Paleocene is mostly limited to aquatic birds. During the Middle Paleocene, however, a group of large, omnivorous, non-flying birds appeared in South America and ruled the land until the Pleistocene Epoch, when humans roamed the earth.4

Known as terror birds , they could range in size from 90 cm to 3 m (35 in to 9 ft), had large, curved beaks, and specialized in slaughtering their prey. Although large, they were heavy and could reach a maximum speed of 50 km/h - while an ostrich can reach up to 70 km/h.

The closest living relatives of the terror birds are believed to be the seriemas. In addition to this, some other present-day birds, such as the mousebirds (Coliiformes), also had their first appearance during the Paleocene.5

Reptiles

Reptiles were undoubtedly the animals most affected by the impacts of extinction. By the end of the Cretaceous period 83% of lLizards and snakes were mostly extinct, and only at the end of the Paleocene did their numbers recover.

Unlike mammals, birds, and other animals, reptiles did not diversify much, but they continued to evolve; by the beginning of the Paleocene, lizards and snakes were no more than 1 m (3 ft) long — it is estimated that the largest snake (Helagras prisciformis) measured 95 cm (37 in)6. However, by the end of the Paleocene there were Titanoboas over 13 m (45 ft) long.

Extinction was proportionally lower in freshwater environments, probably because animals living there had a greater potential to go into dormancy due to their greater efficiency in oxygen production and greater adaptation to large environmental fluctuations7.

It is possible that many freshwater crocodilians survived for this reason, and by the end of the Paleocene, some species, such as Simoedosaurus, could be up to 5 m (16 ft) long. But of all the reptiles, turtles were the least affected - about 89% of the species survived8.

Marine Life

During the Cretaceous, fish were not as abundant and lived in the shadow of large predators. As a result, most of the fish that lived in the open ocean were probably small and rare - like the land mammals of their time.

Although the severity of the K-T extinction varied around the globe, it had a dramatic effect on the oceans, wiping out more than 90% of plankton and causing the entire marine food chain to collapse. Many corals, crustaceans, cephalopods, other mollusks, and even large marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, ichthyosaurs, and elasmosaurs became extinct.

Only 12% of the fish species went extinct, and the plankton that survived was enough for the fish to feed and thrive, becoming much larger and more numerous, occupying all the oceans9.

The Paleocene lasted about 10 million years (66 - 56 Ma), and its end, like other extinctions, was marked by major climate changes. The following epoch is called the Eocene, and although some animals became extinct at the end of the Paleocene, others were able to evolve, diversify, grow, and continue the cycle of life.

Read more:

-

ANELLI, Luiz Eduardo; LACERDA Julio. Dinossauros e outros monstros: uma viagem à pré-história do Brasil. 1.ª ed. São Paulo: Peirópolis – ISBN 978-85-7596-381-4, Edusp – ISBN 978-314-1580-7, 2019. ↩︎

-

Hunter, John. (1999). The radiation of Paleocene mammals with the demise of the dinosaurs: Evidence from southwestern North Dakota. North Dakota Academy of Science Proceedings. 53. 141-144. ↩︎

-

Alvarenga, Herculano M.F. and Höfling, Elizabeth - Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes). Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia [online]. 2003, v. 43, n. 4 [Accessed 17 October 2022], pp. 55-91. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0031-10492003000400001 . Epub 31 Oct 2003. ISSN 1807-0205. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0031-10492003000400001 ↩︎

-

Ksepka DT, Stidham TA, Williamson TE. Early Paleocene landbird supports rapid phylogenetic and morphological diversification of crown birds after the K-Pg mass extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Jul 25;114(30):8047-8052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700188114 . Epub 2017 Jul 10. PMID: 28696285; PMCID: PMC5544281. ↩︎

-

Longrich NR, Bhullar BA, Gauthier JA. Mass extinction of lizards and snakes at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Dec 26;109(52):21396-401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211526110 . Epub 2012 Dec 10. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Apr 16;110(16):6608. PMID: 23236177; PMCID: PMC3535637. ↩︎

-

Robertson, D. S., Lewis, W. M., Sheehan, P. M., and Toon, O. B. (2013), K-Pg extinction patterns in marine and freshwater environments: The impact winter model, J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci., 118, 1006– 1014, doi:10.1002/jgrg.20086 . ↩︎

-

Novacek, Michael J. “100 Million Years of Land Vertebrate Evolution: The Cretaceous-Early Tertiary Transition”. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 86, nº. 2, 1999, pp. 230-58. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/2666178 . Acessado em 18 de outubro de 2022. ↩︎

-

Sibert EC, Norris RD. New Age of Fishes initiated by the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Jul 14;112(28):8537-42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504985112 . Epub 2015 Jun 29. PMID: 26124114; PMCID: PMC4507219. ↩︎